How the Cosmic Perspective Disconnects Us from Our Lives

Note: This is an adaptation of my article Life, The Universe, and Connectedness (2024), published in The Journal of Value Inquiry.

Introduction

Sometimes, we imagine our lives from the cosmic perspective.

Pascal (1670) does so when he writes,

When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in an eternity before and after, the little space I fill engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces whereof I know nothing, and which know nothing of me, I am terrified. The eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.

Similarly, Thomas Nagel (1971) notes,

Think of how an ordinary individual sweats over his appearance, his health, his sex life, his emotional honesty, his social utility, his self-knowledge, the quality of his ties with family, colleagues, and friends, how well he does his job, whether he understands the world and what is going on in it. Leading a human life is a full-time occupation, to which everyone devotes decades of intense concern. This fact is so obvious that it is hard to find it extraordinary and important…Yet humans have the special capacity to step back and survey themselves, and the lives to which they are committed, with that detached amazement which comes from watching an ant struggle up a heap of sand. Without developing the illusion that they are able to escape from their highly specific and idiosyncratic position, they can view it sub specie aeternitatis—and the view is at once sobering and comical.

The cosmic perspective is often associated with questions concerning the meaning of life, our mortality, and our cosmic significance.

Another important feature of the cosmic perspective, the one I want to discuss here, is that taking the cosmic perspective can make us feel disconnected from our own lives. This sense of disconnection can be a rational response to the cosmic perspective.

Feeling Connected to Your Life

Feelings of connectedness centrally involve familiarity, engagement, identification, and feeling at home. Feelings of disconnectedness involve unfamiliarity, disengagement, alienation, and being out of place.

Sometimes, it makes sense to feel disconnected from something. If you discovered that your spouse only married you to get close to your sister, that would warrant a feeling of disconnection from your spouse.

Does it also make sense to feel disconnected from your life—the sequence of events that you go through between birth and death? The answer also seems to be yes. Consider the movie The Matrix (1999), when Neo discovers that he’s been living inside a simulation. It makes sense for Neo to feel disconnected from his life when he discovers this. His own life is something other than what he imagined it to be. It now seems unfamiliar and alien and no longer like home.

It can also make sense to feel disconnected from your own life when you come to reevaluate it in a significant way. A gourmet butcher who becomes convinced by arguments for veganism might suddenly feel disconnected from his life. He will suddenly reappraise many familiar and central aspects of his life: his profession, workplace, and contribution to society.

Let’s now turn to some ways in which the cosmic perspective can make us feel disconnected from our own lives.

Rationality and Value

As mentioned, Thomas Nagel (1971) thinks that the cosmic perspective provides a “sobering and comical” view of our lives. He thinks this because the contrast between the cosmic perspective and our first-person, human perspectives gives rise to a sense of the ‘absurd.’ This is a similar sense of the ‘absurd’, by the way, that was of interest to Albert Camus (1942).

The basic idea is this. We take our lives to be really important. But from the cosmic perspective, we seem about as important as ants seem to us.

This isn’t because we’re small and the universe is huge. It’s also not because we’re short-lived and the universe goes on and on. As Nagel and Bertrand Russell (1903) have pointed out, these facts in themselves are insignificant. Would life become more meaningful if we were huge?

As Nagel seems to suggest, the cosmic view is a point of view from which we really don’t have reason to do one thing or another. In other words, perhaps it’s a perspective from which nothing really matters. But you might not think that seems very plausible. You might think that there are good reasons to act, reasons that simply don’t stand in need of further justification. One such reason might be the alleviation of needless suffering.

Even so, the cosmic perspective might still disconnect us from our lives.

Many of our attitudes and choices are justified by reasons whose strength depends one’s individual identity. Consider my desire to visit Japan. The fact that I desire to visit Japan gives me a reason to visit Japan. My neighbor might also desire to visit Japan. That might give me a reason to get him a ticket, but not as strong a reason.

By definition, however, the cosmic perspective is detached from my personal perspective. Suddenly, I have no more reason to visit Japan myself than I have reason to buy my neighbor a ticket.

That certainly produces a sense of disconnection from my life. Most of my everyday actions do seem rationally underdetermined from the cosmic perspective. As Nagel writes elsewhere, “the problem is not that values seem to disappear” from such a perspective, “but that there are too many of them, coming from every life and drowning out those that arise from our own” (1986).

The Universe’s Bigness

For those of us lucky enough to be safe in our everyday lives, thinking about our cosmic smallness can remind us of our vulnerability in the face of powerful geological and astrophysical forces. We are helpless against things like supervolcanoes, asteroids and black holes. Compared to mountains and stars our lives seem inconceivably brief. This is the sort of feeling evoked by cosmic horror writers like H. P. Lovecraft.

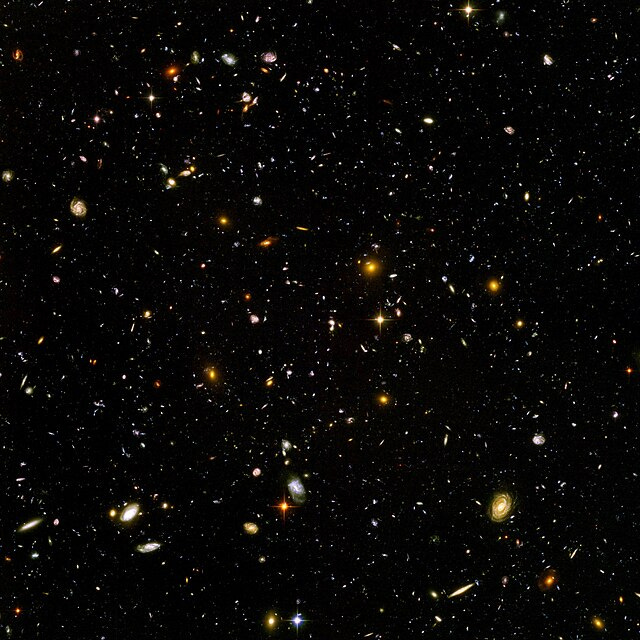

Our homes and towns are (hopefully) safe and familiar. We are surrounded by familiar people, signs, and stores. Zooming out, our countries are full of similar towns. But zooming out further, we’re confronted with a place that’s overwhelmingly made up of hostile environments: acidic atmospheres, burning heat, freezing lows, crushing pressures, and total voids.

Seeing one’s life from the cosmic perspective makes it salient how our lives are fragile and contingent. We feel negated by the largeness of the world. Insofar as we tend to take our safety for granted, such reflections seem to warrant some disconnection from our everyday lives.

Cosmic Insignificance

In one brilliant scene in the Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy Series, a character is sentenced to go into a device called the Total Perspective Vortex, which gives people a view of the “whole infinity of creation and [oneself] in relation to it.” This device is used to make people go insane by showing them how utterly insignificant they are.

Guy Kahane (2014) understands significance not as value or meaningfulness, but as attention-worthiness. He writes, “The intrinsic value of something cannot be changed by its surrounding. But its significance can.”

As such, significance is a zero-sum game. The larger the universe surrounding us, the less significant we are likely to be. On an everyday level, I’m the star of my own life. As David Foster Wallace puts it,

“Everything in my own immediate experience supports my deep belief that I am the absolute centre of the universe; the realest, most vivid and important person in existence….It is our default setting, hard-wired into our boards at birth.”

When I zoom out, I realize that there are billions of other people just as worthy of attention as I am. Zooming out more, I contemplate the possibility that the universe is filled with other lives.

This sudden displacement of oneself from the center of the world is another reason that the cosmic perspective can make us look at our lives with a sense of disconnection.

The Downsides of Disconnectedness

Seemingly, connectedness to one’s lives is important to one’s psychological welfare.

Consider cases where such connectedness is missing, such as with people suffering from depersonalization and derealization disorder (DPDR). Indeed, I was first inspired to write this article by my own past struggles with depersonalization and derealization.

People with DPDR feel “detachment with respect to surroundings” and like an "outside observer with respect to one’s thoughts, feelings, sensations, body, or actions.”

DPDR sufferers also experience disconnection from the habitual ways of evaluating and making sense of things that the rest of us take for granted. They report difficulty “finding worldly objectives…relevant or important” and struggle to “feel the concern or drive to accomplish things in the world,” often being “unable to cope with situational demands or respond adequately in social situations.”

This sort of feeling plays a prominent role in Sartre’s Nausea (1949). The narrator describes losing his grasp on

“the meaning of things, the ways things are to be used, the feeble points of reference which men have traced on their surface…When [scents] ran quickly under your nose…you might believe them to be simple and reassuring…But as soon as you held on to them for an instant, this feeling of comfort and security gave way to a deep uneasiness.”

Disconnectedness and Awe

Disconnectedness isn’t all bad. In small and controlled doses, feeling disconnected from our lives may also benefit us. It can make space for awe.

Take, for example, Carl Sagan’s Pale Blue Dot speech, given about a photo of Earth taken from space:

“Look again at that dot. That's here. That's home…our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light.”

The cosmic perspective disconnects us from our own lives, but it also connects us to the cosmos around us. We develop familiarity and identification of cosmos as, in some sense, our home. This is the sort of feeling often comes with diminished sense of self.

Research suggests that feelings of awe are associated with “increased ethical decision-making… generosity… and prosocial values… prosocial helping behavior and decreased entitlement.” This makes intuitive sense insofar as self-centeredness is particular to the personal perspective.

A little bit of disconnectedness from our lives, therefore, might be healthy. As Bertrand Russell (1935) wrote,

“In our day, it is difficult to imagine a world in which everybody, high and low, educated and uneducated, was preoccupied with comets, and filled with terror whenever one appeared…The cause of the change in our attitude is not merely rationalism, but artificial lighting. In the streets of a modern city the night sky is invisible; in rural districts, we move in cars with bright headlights. We have blotted out the heavens, and only a few scientists remain aware of stars and planets, meteorites and comets. The world of our daily life is more man-made than at any previous epoch. In this there is loss as well as gain: Man, in the security of his dominion, is becoming trivial, arrogant, and a little mad. But I do not think a comet would now [help]…a stronger medicine would now be needed.”

The cosmic view, while disconnecting us from our lives, can also foster humility and awe.